Home | News | Books | Speeches | Places | Resources | Education | Timelines | Index | Search

By 1861 presidential inaugurations had well established customs. The outgoing president usually escorted the president-elect in a procession down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol, starting at Willard's Hotel on 14th Street. On Lincoln's inauguration day 16-year-old Julia Taft and her mother watched the procession from a hardware store because the Capitol might prove too dangerous. "As we took our places a file of green-coated sharpshooters went through up to the roof. The whisper went round that they had received orders to shoot at any one crowding toward the President's carriage."

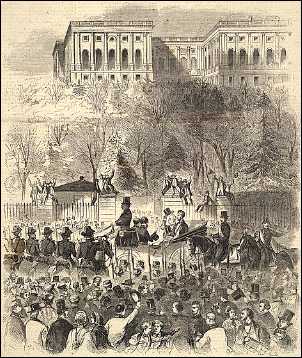

U.S. Capitol on Inauguration Day, 1861

Library of Congress

Abraham Lincoln's First Inauguration

Shortly before Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, 1861, a political supporter recalled the turbulent atmosphere of Washington, D.C. "The air was still thick with rumors of 'rebel plots' to assassinate Mr. Lincoln, or to capture him and carry him off before he could take hold of the reins of government."The burden of Lincoln's safety fell on the aged shoulders of Lieutenant-General Winfield Scott, celebrated war hero and head of the U.S. Army. He wrote of this duty as "the most critical and hazardous event with which I have ever been connected." Not only was Lincoln's life endangered by Southern secessionists, but Scott himself received many death threats if he "dared to protect the ceremony by military force." Scott rounded up as many soldiers as possible from his scant forces, so when Lincoln rode to the Capitol, a reporter noted, "His carriage was closely surrounded on all sides by marshals and cavalry, so as almost to hide it from view."

Julia watched Lincoln and his predecessor ride by in an open carriage. She admitted she "suffered a pang of sorrow at the going of that lovable gentleman of the old school, President Buchanan. Up to that time he had been my ideal of what a President should be." She noticed the crowd seemed hostile toward Lincoln and heard a woman remark, "There goes that Illinois ape, the cursed Abolitionist. But he will never come back alive."

Lincoln pulled out a pair of reading glasses, secured his manuscript with a gold-headed cane, and tried to lay down his new silk hat. Schurz said, "I witnessed the remarkable scene when Lincoln, about to deliver his inaugural address, could not at once find a convenient place for his hat, and Douglas took that hat and held it like an attendant, while Lincoln was speaking." A reporter wrote that Douglas responded to the speech saying, "Good," "That's so," "No coercion," and "Good again."

Lincoln Enroute the Capitol, March 4, 1861

Library of Congress

When the presidential party reached the Capitol, the next stop was the Senate chamber. There the outgoing vice president, John Breckinridge, spoke briefly and his successor, Hannibal Hamlin, took the oath of office. Mary Lincoln's cousin witnessed the scene: "Judges in their silk gowns, Senators, Members of the House, and the members of the diplomatic corps, in their brilliant uniforms, were assigned prominent places ... Mrs. Lincoln and her party occupied the diplomatic gallery." The audience in the Senate chamber followed Lincoln to the Capitol east front; modern inaugurations use the west front. Senator Edward D. Baker, a longtime friend of the Lincolns, introduced the president-elect to a crowd of about 25,000 people. Carl Schurz, another political friend, watched the proceedings intently. "I saw Lincoln step forward to the desk upon which the Bible lay -- his rugged face, appearing above all those surrounding him, calm and sad."

He scrutinized three other dignitaries on the platform. The first was Senator Stephen A. Douglas, the new president's "defeated antagonist, the 'little giant' of the past period, who, only two years before, had haughtily treated Lincoln like a tall dwarf." Douglas proved a vigorous political rival in Illinois, famous for the joint debates he and Lincoln held during the 1858 Senate race. Douglas won the election and challenged Lincoln for the presidency, but became a bit player in the great inaugural drama. Only a few months later he would die in Chicago.

Schurz also observed James Buchanan, "the man who had done more than any other to degrade and demoralize the National Government and to encourage the rebellion, now to retire to an unhonored obscurity..." As for 83-year-old Roger Taney, he said, "I saw the withered form of Chief Justice Taney, the author of the famous Dred Scott decision, that judicial compend of the doctrine of slavery, administer the oath of office to the first President elected on a distinct anti-slavery platform." Taney died in office three years later, and Lincoln filled the position with abolitionist Salmon Chase.

Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, sat behind Lincoln during the speech, "expecting to hear its delivery arrested by the crack of a rifle aimed at his heart, but it pleased God to postpone the deed, though there was forty times the reason for shooting him in 1860 that there was in '65, and at least forty times as many intent on killing or having him killed. No shot was then fired, however; for his hour had not yet come."

The ceremony ended with the oath of office, breaking the tension. Said a young New Englander, "When the address closed and the cheering subsided, Taney rose, and almost as tall as Lincoln, he administered the oath, Lincoln repeating it; and as the words, 'preserve, protect and defend the Constitution' came ringing out, he bent and kissed the book [Bible]; and for one, I breathed freer and gladder than for months. The man looked like a man, and acted a man and a President."

Across town, Charles Francis Adams, Jr. remarked, "the long, eager, anxious struggle was over. A Republican President was safely inaugurated." Walking home, he encountered Senator Charles Sumner, who thought Lincoln's speech was "best described by Napoleon's simile of 'a hand of iron and a velvet glove.'" When Adams reached home he found his father "in high glee" over the inaugural. "Thus, that day, every one was, as [Secretary of State] Seward predicted they would be, 'satisfied.'"

That outlook may not have been shared by Buchanan. He told a reporter, "I cannot say what he means until I read his Inaugural; I cannot understand the secret meaning of the document, which has been simply read in my hearing." How much he actually heard was conjecture, for he appeared sleepy and "sat looking as straight as he could at the toe of his right boot." As for Douglas, he told a reporter that Lincoln "does not mean coercion; he says nothing about retaking the forts, or Federal property -- he's all right." But to another, he hedged, "Well, I hardly know what he means. Every point in the address is susceptible of a double construction; but I think he does not mean coercion."

On the day after the inauguration a local editor wrote, "In this city there are no two opinions relative to the ability of President Lincoln's inaugural. All regard it as being a State paper of great force of reasoning; while all friends of the Union of all parties assent to most of its conclusions. The few disunionists left among us to-day ... of course fail to see propriety in its exposition of the President's obligation to execute the laws of the land as far as he has power to do so."

Response from Southerners was predictably negative. A New York Times reporter wrote, "The Inaugural Address is the subject of much excited comment among Southern politicians here. Hon. John Bell is said to pronounce it a declaration of war, and to declare that he shall urge Tennessee to prepare for conflict. This is very doubtful. Some Southern men consider it a hostile paper clothed in the most pacific and conciliatory language, or, in other words, that it presents a basis for either war, or peace."

Related Links

Lincoln's First Inaugural Address

Lincoln's Inaugurations

Lincoln's Second Inauguration

Lincoln's Second Inaugural AddressRelated Reading

Adams, Charles Francis, Jr. Charles Francis Adams, 1835-1915 An Autobiography. Boston:Houghton Mifflin Co., 1916.

Bayne, Julia Taft and Decradico, Mary (intro). Tad Lincoln's Father. Bison Books, 2001.

Cole, Donald B. and McDonough, John J., ed. Witness to the Young Republic, University Press of New England, 1989.

Commager, Henry S. editor. The Blue and the Gray. Indianapolis, 1950.

Gobright, Lawrence Augustus. Recollections of Men and Things at Washington. Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger, 1869.

Grimsley, Elizabeth Todd. "Six Months in the White House," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 19 (October 1926 - January 1927)

New York Herald, March 4, 5, 1861

New York Times, March 5, 6, 1861

Schurz, Carl. The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1909.

Scott, Winfield. Memoirs of Lieutenant-General Scott, LLD. New York: Sheldon, 1864.

Washington Star, March 4, 5, 1861

Wilson, Douglas L. Lincoln's Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words. Alfred A. Knopf, 2006

Home | News | Education | Timelines | Places | Resources | Books | Speeches | Search Copyright © 2024 Abraham Lincoln Online. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy